“Just do it”… but how? Reflections on becoming a grounded theorist

As I reach the final stages of my doctoral research, and am close to having developed a substantive grounded theory, I find myself looking back at my journey from bioscientist to grounded theorist. When I first started my project and I was researching grounded theory as a methodology (or is is a method? or both? or neither? One of the many issues I grappled with) it was enshrouded in mystery and complexity. Following recent discussions with newer members of the group of researchers at ARU doing a grounded theory project, I now find myself answering questions about my process, and I find people within and outside of my institution looking to me for advice. Not only does this make me think about how far I have come, and how long it took for me to "get it", but it also results in major impostor syndrome kicking in.

Grounded theory (GT) at first made very little sense to me. Glaser's mantra of "Just do it" sounds fine in theory, but in practice it is not that easy. There is very little practical advice for novice researchers, and the bit of practical advice that is available predominantly focuses on constructivist GT, and a bit on Straussian GT. For those opting for the Glaserian flavour however, the main advice is to "read the book" (meaning one of the textbooks authored by Glaser himself) and to "just get started and do it". But I found myself wondering where to start, how to start, and how to know whether I was doing it right. Going by the number of published papers aimed at novice researchers or discussing decisions made by novice researchers (e.g. Evans, 2013; Ahmed & Haag, 2016; El Hussein et al, 2017), and the wide range of workshops available, I was not alone. Add to this the fact that I am a bioscientist venturing into the world of qualitative research, getting started with GT was not just out of my comfort zone, it was in a completely different world where comfort zones don't exist! I was very, very lost.

In response to this I did what every good doctoral researcher does... I started reading. I followed the advice, and started reading Glaser's textbook, starting with "Discovering Grounded Theory", the original textbook. I still don't know whether it was me, but this, and some of the other books by Glaser, was one of the most inaccessible textbooks for those new to a method I have ever read. It took forever to get through some of the books that are considered basic, and I got more and more disillusioned. I started questioning whether I would ever get my head around the method(ology), and I still didn't understand how to translate the theory from the book into the practice of doing research. I was wrestling with "what does coding look like?", "how do I know my codes are right?" and "what is conceptualising?" and "how will this ever pass muster in a viva?", whilst at the same time trying to figure out how to interview, whether or not to record interviews (Glaser (1998) most definitely says no), and a lot of other things. It wasn't until I found some methodology papers written by grounded theorists other than Glaser that it somehow started to make a bit of sense (e.g. Engward, 2013; Timonen et al. 2018; Birks et al., 2019) .

It turns out I was overthinking it completely. Once I got over the fact that starting a GT study would involve a lot of uncomfortable unknowns (us bioscientists don't like not knowing...) I did my first interview. It was hard. I felt like I did not have a clue what I was doing. However, I got through it and managed to get an hour's worth of interview data which now needed coding. I was looking at my transcripts (yes, I did end up recording the interviews and using the transcripts, purists close your eyes now!) and had no idea what to do with them. I decided to read some more. I got stuck on the "you should use gerunds for your codes" element, and it took a while to figure out that this was optional, and that it is perfectly fine for initial codes to be descriptive and to use the participants own words (see e.g. Harris, 2015). In the end I simply started going through the transcripts and started describing what behaviours my participants were telling me about. I used simple words, intuitive to me, that clearly outlined what was happening, such as "asking a colleague" or "needs training". I remember thinking "hey... maybe I can do this". Once I had done three interviews like this, I started seeing some rudimentary patterns. It turns out that some of my various descriptive initial codes described very similar behaviours, and that when taking these behaviours together as a group, where was an overarching idea. For some behaviours this was easier than others, but I was onto something here...

Going back briefly to the notion of conceptualising, this was something that took a while to get my head around. Like reflective and reflexive writing, conceptual thinking is not something that comes naturally to us scientists, because we don't get taught it during our training. I had to go back through my first four transcripts and look at my codes again to make a bit more sense of this. In the end, I settled for the following approach: Where multiple descriptive codes were similar, or described similar things, I asked myself "what are these codes an example of?", "What behaviour am I seeing here?" and "Can I take one step away from this?". It was this last question that in the end made it click. Turns out that conceptualising is not that hard, but you can't learn it from reading a grounded theory book (or I couldn't at least), and it is OK to make up words if you can't think of any.

So to recap: I was now four or five interviews in, I figured out that my patterns were sensible, and that if I took a step away from the direct behaviour I had a concept. I re-analysed the transcripts to make sure I hadn't missed anything, and from here on I coded new transcripts with the existing concepts in mind. Did it fit in one of them? If so, great, if not, assign a decsriptive code and get back to it later. This was making a bit more sense now. But where would I go from here? How does one go from concept, to category, to basic social process? How far can you take this conceptualising lark? I read some more. I landed on a paper by Qureshi & Ünlü (2020) which broke down the coding process into some very logical steps. Mindful to not be pushed in boxes, I read the paper with an open mind. What was particularly useful were the examples used in the paper. They clearly demonstrated increasing levels of conceptualisation, while using simple language that I as a mere novice qualitative researcher could understand. In the end I didn't adopt the tool advocated in this paper, but I was a lot clearer on conceptualisation. The main thing holding me back now was my lack of (what I thought) suitable vocabulary. I had lots of ideas floating through my head, but I couldn't find the right words. Until one day, where it suddenly clicked.

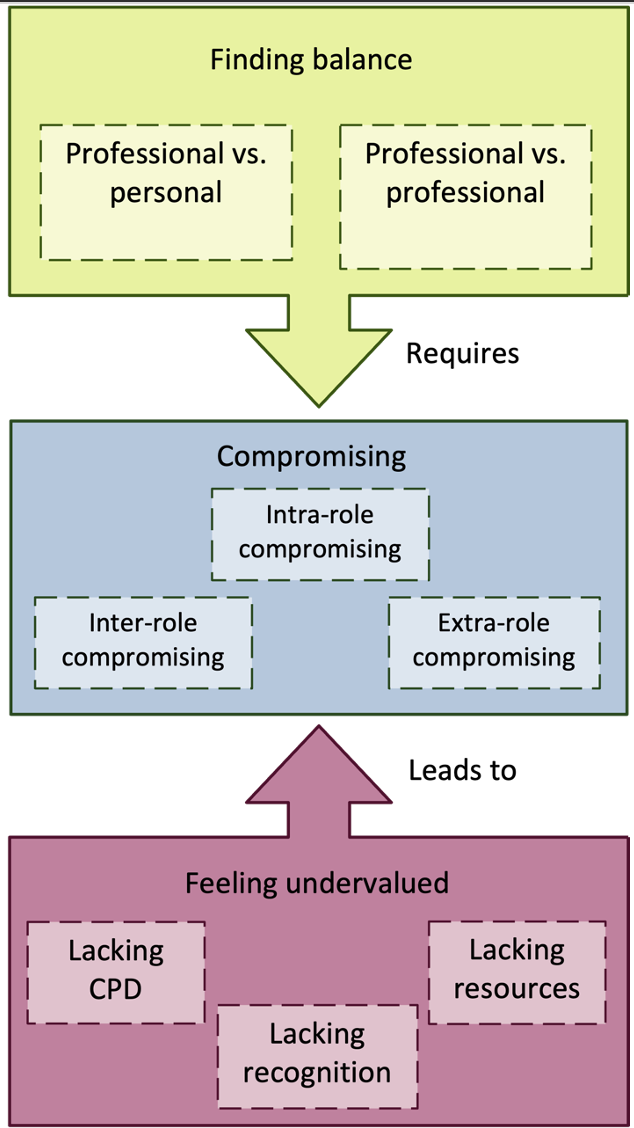

I remember the moment. I was riding my bike into work, and somewhere midway my thoughts drifted to my most recent interview. I found myself thinking about what the participant was actually telling me. What were they doing, and what were they not doing? How were they doing their job, and why? Suddenly it was there. The candidate was describing balancing their many responsibilities (even though they didn't use this word directly. "Conceptualising", remember...). Thinking back, this was the same for all participants interviewed to date. In their own way, they were all describing the process of balancing their responsibilities. Thinking about this more, I started wondering about how they were finding balance. Turns out they were all describing in various ways how they were making compromises to find balance...

Boom! This was it. I was conceptualising without realising it, I was explaining the concepts without realising it. I was onto something! It was right under my nose all this time. I had an emerging theory. When I got to work I wrote everything down in a memo and made a sketch before I got changed out of my cycling kit. My office smelt rather sweaty that day...

From here onwards, my interviews focused on testing my theory. I had to do this in such a way that I didn't lead my participants, but I now had some new areas to focus my questioning and exploring on. I was excited, and then I realised I didn't have a clue how to move on from here... Queue brilliant supervisor. During a supervisory meeting, and a follow-up phonecall, my supervisor put my mind at ease that I should just go with the flow like I had been doing. I did some more interviews, and I heard nothing new. I remember asking myself "Is this it?" I could now start focusing on explaining my theory, and start linking it to the literature. I had an answer to my question, and now I need to start figuring out how the answer fits in.

This is where I am now. I have just started the theoretical coding phase. As with the preceding phases this is scary as I haven't got a clue what I am doing really. However, the thought that I made it this far, and that my thinking so far makes sense, means that I am sort of happy that I can do this. It was an off-the-cuff comment my supervisor made during a call last week that gave me confidence. She said "you are thinking like such a grounded theorist". Who would have thought someone would ever say this about me as a researcher. Definitely not me three years ago. Maybe Glaser was right... maybe "just doing it" is the way to get started. Still, some clear illustrative examples and practical instruction would have been nice. Hopefully I can provide this in the future, and hopefully this writing gives you, the reader, some confidence that it can be done.

My take home message is as follows: don't be too worried about making mistakes, and don't worry too much about the various "-ologies". They have little bearing on the "doing" of grounded theory, and can be addressed later. Start collecting your data, and code using your own words in the beginning. The concepts will follow.

Keep on researching, and get in touch if you want to discuss. Alternatively, join the party at our regular ARU GT Seminar, which is open to all and involves presentations by both established GT experts as well as doctoral students doing GT. Follow me on Twitter to keep up to date.

N.